USDA Reorganization: Regulatory Capture by Design

The Jekyll Island of the Department of Agriculture.

Some few government agencies have a bias towards doing things – what Caleb Watney calls the operational mindset. The Census Bureau, for instance, exists to take a census. Most agencies do not, which is often a consequence of the way they are organized.

In Agency Missions, I discuss two ways to organize agencies and the typical mindset that results from each. One way to organize agencies is by subject matter – for example, the Forest Service does everything related to the subject of forests (including functions such as research and administration). Another is by function – for example, the National Science Foundation undertakes the abstract function of research (and researches many subjects). A subject matter agency has a concrete mission, and therefore tends to have an operational mindset. A functional agency tends to find this mindset unnatural.

In The High Tide of Reform I use the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a case study of these two types of agencies. Its 1942 reorganization turned its subject-matter agencies into functional agencies, which was almost immediately followed by the department losing its political entrepreneurialism and being captured by the agricultural interest groups. The reorganization demonstrates the harm of removing an operational mission.

But the history supports an even stronger claim: the decline of USDA’s operational mindset was not only a consequence of functional reorganization – it was an intended consequence. The farm lobby had strongly endorsed functional reorganization in order to make the USDA bureaus more blindly responsive to the farmers lobby, and therefore less mission-oriented.

So does an operational mindset lead to greater state capacity? Almost certainly. Even the opponents of state capacity agreed – namely the farm lobby. The farm lobby debated USDA organization using these concepts, and eventually won control over the previously-independent bureaucracy.

The lobby’s ultimate success in capturing the bureaucracy didn’t happen overnight. Their victory in the 1940s was laid much earlier, through their planning in the 1920s.

Live at farm aid, 1925

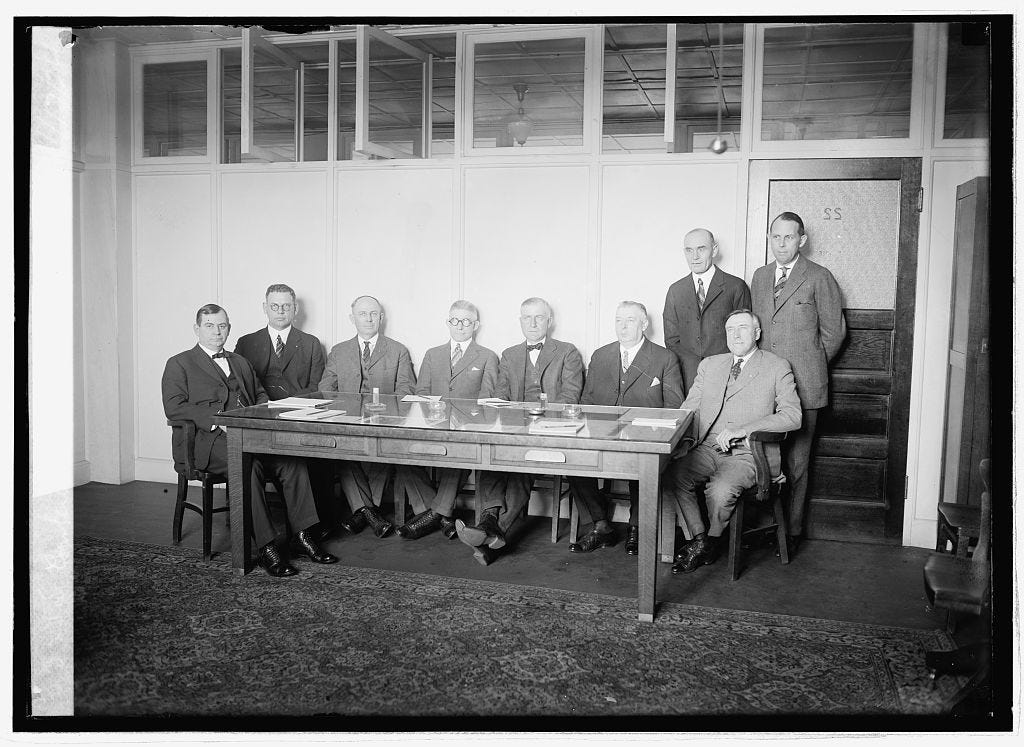

For American farmers, the 1920’s were a troubled decade, marked by turmoil in a time of prosperity. In 1925, President Coolidge responded by convening a farm conference, which studied the problems facing American agriculture and suggested ways to aid farmers. Among much else, they considered the question of departmental organization at USDA.

Their discussion is so instructive that I quote it at length:

The activities of many different departments and agencies of the Federal Government have a direct bearing upon agricultural welfare. In general, these activities may be divided into two major types: namely, service functions and regulatory or law-enforcement functions. Service activities consist essentially in the accumulation and dissemination of information concerning all factors which enter into the production, distributing, and consumption of agricultural products, and advice and assistance in putting this information into practice. Regulatory functions consist essentially in the interpretation and enforcement of laws and regulations designed to protect the interests of both the producers and the consumers of agricultural products.

In many of the Federal departments, both the service and regulatory functions dealing with the same commodity or industry are lodged in the same bureau, offices or personnel. This has many disastrous effects. In the discharge of the regulatory or police functions, officials of the departments are sometimes required to adopt the judicial attitude, sometimes a combined judicial and prosecutorial attitude, but more often an exclusively prosecutory. This attitude inevitably leads to a feeling of antagonism of interest between the department officials and the individual citizens or organizations which come into contact with the Federal agency. Such a feeling is the exact opposite of that which must maintain if the service functions of the agency, which depend upon a community of interest in advancing the welfare of the industry, are to be effectively discharged. Many of the instances of unsatisfactory administration of government activities touching agricultural welfare, which have been brought to the attention of the conference, have been clearly and directly traceable to the feeling of antagonism, instead of community of interest, between the government officials and the individual or group which was seeking government assistance.

The Conference, therefore, recommends that in all branches of the Government, the service functions and the regulatory functions be separated as completely as possible in organization, personnel, and action.1

In some respects, this report was nothing new: farmers had (naturally enough) advocated for a more pro-farmer USDA since its creation. But this presidential conference was, so far as I know, the first chance for the farm lobby to think through what a favorable reorganization would look like. I would tentatively say that it was even the first major discussion of how departments should, in principle, be reorganized.2

Regardless of if the report directly influenced the 1942 reorganization, it was an early statement that the farmer’s lobby would support functional reorganization, and was unique in explaining their reasoning at length.

Reorganization and its consequences

The passage shows that the idea of “functional organization” or “operational mindsets” aren’t modern ideas grafted anachronistically onto the past: they were precisely the concepts that interest groups used to discuss bureaucracy, even in the 1920s.

The farm conference rejected subject matter agencies that combined service (i.e., grants and education) with regulation and research. For instance, the Bureau of Entomology researched insects, condemned diseased crops, and educated farmers on preventing infestations. The farm conference felt that these were incompatible goals: the farmers would be far more positive about the agency if it only gave them grants and education, without also regulating them.

Accordingly, they advocated that regulatory and service functions be divorced. The only logical way to reorganize the department (under their scheme) would be to group regulatory agencies together and service agencies together; that is, to have a some number of agencies devoting to regulating farmers, and some number devoted to distributing aid. Through this functional reorganization, the agencies that distributed aid would form a “community of interest” with the farmers.

Now, if the goal is a “community of interest” with the farmers, it follows that the goal is not some operational mission. The opponents of functional reorganization made this even more explicit, as in Gifford Pinchot’s argument against similar (proposed) reorganizations:

If anything is proved in government work, it is that to separate administration and research means bad administration every time. As good an illustration as I know is the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior. Research it had none, and its mishandling of the public lands became a scandal, the stench of which is with us yet.3

Swap out “regulation” for “research”, and his argument holds exactly. Previously, a USDA agency had a mission, perhaps entomology. Its mix of regulation and service gave its regulators greater prestige, while also keeping the interest groups at a certain distance from the grant writers. But once USDA bureau lost their operational missions, they could only passively aid their interest groups; accordingly, their independence atrophied after the reorganization. As Pinchot would say, it meant bad administration.

Leading up to the reorganization, there was no debate about the effects. All involved believed that functional reorganization would lead to greater interest group influence and less agency entrepreneurialism. They only disagreed about if this was good or bad.

Eventually, the reorganizers got their wish, and the farm lobby got its desired influence shortly thereafter. But today we might turn that on its head – subject matter reorganization could help the government do things.

As quoted at length in a Virginia agricultural commission’s report. I wish that I had the original source! But the fact that state level commissions were citing the report as inspiration for reorganization is, in itself, quite important.

At the state and local level, there was some discussion of how departments should be organized, where departments were being created from scratch. There were also discussions of reorganizing federal departments by moving bureaus from one department to another. But this appears to be the first extended discussion of reorganizing a single federal department according to some systematic theory. Leonard White in The Principles of Public Administration vaguely implies that it is the first such discussion.

Quoted in The High Tide of Reform. My general assertions about USDA and its interest groups are better documented in that piece, as well.