Uncle Sam's Problem Children

The five most problematic types of government programs according to Herbert Emmerich. A new series on efficient executive branch reorganization.

Previously I’ve written about the government’s most striking successes. It’s now time for a series on government failures and what they can teach us. And not one-off failures, either. This post introduces a new series on efficient executive branch reorganization – approaches for reorganizing the government to address the most stubborn problems in public policy.

So what are the worst of the worst in government policy, these evergreen problems? Herbert Emmerich has an answer.

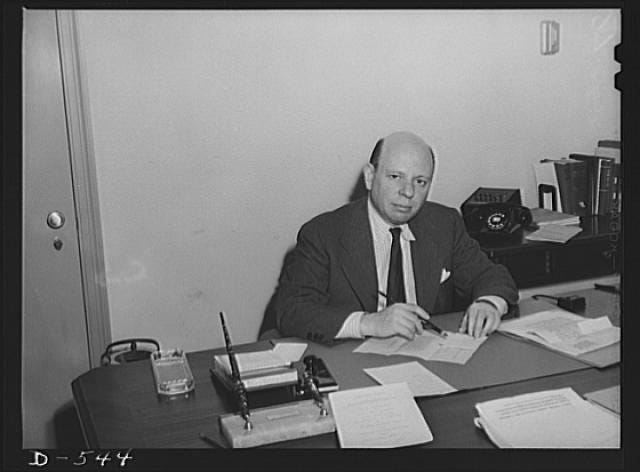

Herbert Emmerich was a longtime civil servant and academic. He ran several agencies during the 1930s, eventually becoming executive secretary of the War Production Board during World War II. He was chairman of the Public Administration Service (an association of public administrators), and consulted for international organizations such as the United Nations. In short, he saw it all from every angle. In his last year of life, he wrote the book Federal Organization and Administrative Management, which summed up his lifelong thoughts on public administration.

His chapter on the organization of the executive branch discussed what he considered to be the thorniest issues. In particular, he highlighted five agency structures and types of programs as being uniquely and consistently problematic:1

Independent regulatory agencies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the Federal Communication Commission (FCC).

Government-owned corporations, such as Fannie Mae or the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

Intergovernmental programs, including aid to states and programs that are jointly administered by federal and state government (such as disability claims or Medicaid).

Programs administered by contractors. These include everything from Head Start, whose programs are run by nonprofits, to military research, which is often conduction by nonprofits such as RAND.

Programs requiring special external coordination. For instance, national security is coordinated in the White House by the National Security Council, which ensures that diplomats, spies, and military officers are all marching to the beat of the same drum.

Old hands in Washington would agree that these programs cause no end of headaches. But why is this the case?

Schoolhouse Rock and its discontents

To understand what makes these areas problematic, consider what makes ordinary government programs unproblematic.

High school civics class teaches how a typical and unproblematic government program works. In this “Schoolhouse Rock” theory of public administration, a government program begins with Congress identifying an issue that is a federal responsibility. It then passes a law that sets a specific goal and empowers an agency to accomplish it. The President then picks the people to run the program, who implement the goal through directing the federal bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, the other two branches of government provide oversight. Congress holds hearings and wields its greatest influence through its “power of the purse”, the ability to cut off funds to misbehaving agencies. The judiciary stands above the fray and polices government actions, thereby ensuring that the constitutional and other legal rights of private citizens are protected.

Experienced observers could find at least a dozen problems with this oversimplified story. Nonetheless, for many government programs it is more or less an accurate description.

This story is more than a theory of civics – it is a theory of management. It starts with some specific task being identified from a well-defined set of federal issues, which is then made concrete by a carefully drafted act of Congress. Once the goal is identified, the program is carried out via a chain of command running from the President to a cabinet secretary to whoever is managing the specific program. External oversight is provided by Congress, which reviews the overall adequacy of implementation (somewhat akin to a corporation’s board of directors), while the judiciary reviews the legality of policy (somewhat akin to a corporation’s external auditor).

But by contrast, the five areas above are uniquely problematic because they are the least similar to the Schoolhouse Rock theory of government. They deviate the most from this theory of management and yet they must be managed, leading to intractable arguments over the form management should take instead. Consider each of the five areas in turn and how they deviate from a naive theory of government.

The five problem children

Regulatory agencies – Regulatory agencies set the rules of the game for particular industries. For example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates cell phones, radios, and other uses of the radio spectrum. Regulatory agencies typically have a range of responsibilities in order to carry out this mission.

Primarily, regulatory agencies typically write general rules for their industry – for instance, FCC sets rules about which parts of the radio spectrum are reserved for radios vs for cell towers. Generally, regulatory agencies review and approve permits – for instance, FCC reviews applications from people who want an amateur radio operator’s license. Regulatory agencies adjudicate complaints against the companies they regulate – for instance, FCC takes action against phone companies that are responsible for spam phone calls. Additionally, regulatory agencies sometimes administer various grant programs or have other assorted tasks.

These regulatory agencies tend to be structured as independent commissions who vote on the rules and the adjudications. That is, a bipartisan commission of about five people run the agency, which is not part of a larger cabinet department. The commissioners are appointed for an extended period of time. This structure raises several issues.

The agency’s independence weakens presidential oversight. The president picks a bipartisan board to run the agency, rather than choosing a trusted lieutenant to have full authority to run it. Not only does the President have less influence, but there is less clear of a chain of command overall in this multi-headed agency.

The agency’s regulatory actions are less subject to judicial oversight than other government actions. When agencies adjudicate complaints, they often have procedures that are similar to courts, yet lack independent judges. For instance, if FCC wants to revoke the license of a radio station, it has a trial-like procedure where the radio station’s lawyer can present evidence. The civil servant running this procedure is not a judge, but an employee of FCC (the agency attempting to take away the license). It is an disputed question if these procedures are an acceptable substitute for real trials.

Finally, regulatory agencies often (but not always) fund themselves with fees, which weakens Congressional control. Agencies charge the public fees to, e.g., file applications, which makes them less dependent on Congressional appropriations. This, in turn, weakens Congress’ power of the purse.

Government corporations – Government corporations are agencies whose work is similar to the work of private corporations. For instance, they might originate loans, offer insurance, or provide services to consumers. Federal examples might include: the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which sells electricity in the Southeast much as any electricity generator would; Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which buy mortgages from banks and package them into securities; and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which charges banks fees to offer them deposit insurance, thereby insuring that an average person does not lose money if a bank goes bankrupt. States and localities often have government owned water or electric facilities.

Government corporations often have substantial autonomy and are generally not part of cabinet departments. They are generally run by a board, which sometimes picks the head of the agency (although the President sometimes picks the head). Often, nearly their entire funding comes from their fees and other revenue. Once again, issues arise from the organization of these agencies.

Autonomous government corporations often lack a clear chain of command, as they are rarely part of larger cabinet agencies and (sometimes) the president does not pick their director.

Government corporations receive revenue from their operations, which greatly weakens Congressional oversight. For instance, TVA gets its funding through selling electricity, which means that Congress has relatively little influence over it (compared to other agencies).

Intergovernmental programs – Intergovernmental programs are those that are jointly administered between the federal government and state/local government. Often these are aid programs where, for example, the federal government might aid states that are already building roads by offering to cover part of the cost. In other cases, federal programs are formally administered by the states. For instance, Medicaid is a federal program that provides health insurance to the poor. The federal government sets Medicaid eligibility and coverage standards and provides funding, but the states design and implement the programs.

Here, the common problems arise from the nature of these programs rather than the structure of agencies.

Intergovernmental programs have a weak chain of command and weak oversight across the board. When the states and the federal government are both in charge of an issue, then nobody is truly in charge of it. For instance, when the federal and state governments are jointly funding highways or other transit programs, both parties are more willing to be wasteful because they are wasting other people’s money. When intergovernmental programs fail, Congress and the president lack a unique person or agency to hold accountable.

These divided responsibilities not only create problems of oversight but also weaken the system of federalism. The more cooperation there is between the federal and local governments, the muddier is the concept of unique, clear roles for each layer of government.

Programs administered by contractors – Contractor administered programs are programs that the federal government farms out to a third party rather than performing itself directly. Sometimes this entails outsourcing simple office functions, such as when agencies pay contractors to update IT systems rather than using their own IT team. Sometimes the purposes are broader as, for example, how the military contracts with RAND to serve as an official think-tank. In some cases, the role of contractors is extraordinarily expansive and they administer nearly the whole of a government program. For example, the FCC administers a program called the Universal Service Fund. Rather than administer this program itself, FCC pays a nonprofit – namely the Universal Services Administrative Corporation (USAC) – to carry out the work.

As above, problems arise from the nature of the program.

Contractual programs can lack any sort of chain of command and almost entirely escape oversight. Contractors are not part of the bureaucracy at all and are therefore minimally responsible to the president, Congress, or the judiciary.

Programs requiring special external coordination – In some cases, many agencies might be involved in the same policy area, thereby requiring external coordination. For example, the National Security Council (NSC) coordinates the nation’s spies, diplomats, and military officers to ensure they have a consistent vision of foreign policy (namely, the President’s). Similarly, the legal policies of government agencies are coordinated by the Department of Justice so that the government can speak with one voice – it would be somewhat absurd if two agencies were arguing against each other in court.

Here, the problems arise because interagency cooperation is difficult. Agencies would always rather have the freedom to push their own viewpoint and dislike being coordinated by an external entity.

Efficient reorganization: a series

This post introduces a new series on efficient executive branch reorganization. These five areas are the most intractable problems, so efficient ways of reworking them offers the greatest value. How can these programs and agencies be restructured or reorganized to minimize the problems mentioned above? How can these corner cases be made to conform as closely as possible to the Schoolhouse Rock theory of government?

Although executive branch reorganization is in the news (due to DOGE), most of the current proposals – cutting headcount and eliminating minor agencies – would make government organization only marginally more efficient, at best. This series aims, by contrast, to get at the heart of the matter.

Each type of program or agency will receive one or more posts. I’ll lay out the history of the problem, the history of proposals for reform, and the (not too extensive) theory of public administration needed to make sense of it all. I’ll sum up by indicating what reorganization would look like today if the goal is to bring these programs/agencies closer to the Schoolhouse Rock view of government.

Even if these problems can never be solved, the lessons of history and administrative theory show us how they might be improved.

Herbert Emmerich, Federal Administration and Administrative Management (University of Alabama Press, 1971), 11.

A thought on contractor accountability: rules for hiring and firing currently make it extremely difficult to fire agency staff for matters of performance. By contrast, I gather it is easier to terminate a contractor’s contract. In this scenario, contractors have more direct (but blunt) accountability to agencies than some of agencies’ own staff.

If there is one lesson of these times, it seems to me it is that the regulatory agencies should be as little accountable to the President as possible. The bigger lesson though is that the Presidency itself is a deeply flawed idea. No one person should have that much power.