TWI versus Gulick: From implementation to "policy planning"

What I want to know is: Where did the process charts go?

I have previously written about how the federal government once trained managers to focus on implementation.

In my post Eisenhower’s Bureaucrats, I explained the approach to managerial training that the federal government developed, which they called work simplification.

In my post The Snyder Cuts, I explained how Treasury Secretary Snyder put work simplification to practice at IRS: he modernized IRS’s IT while cracking down on corruption.

This raises a rather obvious question: if this approach was so good, why did the US abandon it?

As with all social trends, there were many reasons. So here I will note only one: competing theories about the purpose of government management.

Two theories of management

A surprising amount of government reform is the adoption of management fads. In this respect, the past was no different than the present.

During the Great Depression and second world war, the federal government’s administrators cast about for theories of management. Two ideas proved influential, and both were borrowed from private industry.

One was Luther Gulick’s POSDCORB idea, which was borrowed from French industrial management. The other was the Work Simplification method, which was borrowed from Training Within Industry (TWI), an industrial training program from WWII. The former focused on abstract policy from above, whereas the latter focused on bottom-up and iterative improvement.

The federal government eventually rejected TWI-based approaches in favor of policy planning from on high. Ironically, TWI ultimately developed into lean manufacturing in Japan; to contemporary eyes, the approach from the 1940s was more modern than what replaced it.

Gulick and POSDCORB

The ultimate victor in this struggle for federal management was Luther Gulick: an administrator, academic, and reformer. In his long 101 years of life, he achieved an enviable record – not least, he became a major figure in public administration despite having only written two or three article that anyone has read.

Among those articles was the immensely influential Notes on the Theory of Organization. This article poses the question, “What is the work of the chief executive? What does he do?” And according to Gulick, “The answer is POSDCORB”.1 This made-up acronym illustrates the major functions of the executive:

POSDCORB

Planning

Organizing

Staffing

Directing

Co-ordinating

Reporting

Budgeting

Gulick adopts this idea from the managerial theories of Henri Fayol. Although Gulick is discussing the President, this is a general theory of management that could be applied at any level of any organization.

It is unnecessary to discuss the elements of POSDCORB, except that this managerial style is strikingly top-down and totally non-operational. There is no suggestion that the executive should understand anything at all about his organization’s work, much less that he should empower low-level workers.

These were intended as nearly the only issues for an executive to consider. Moreover, Gulick held that each function should be institutionalized: the executive should have a budgeting agency, a planning agency, a personnel agency, and so forth. These support agencies would help the executive make strategic decisions without the distraction of operational issues.

Gulick’s theory was immensely influential: he wrote the article as a background memo for FDR’s Brownlow Committee, which studied the executive branch and proposed reforms to increase its efficiency. Most of their proposals were rejected, but the proposals on executive management were largely adopted.2

The proposals were even more influential over the longer run. The reports were careful analyses, skillfully written by distinguished academics. The prestige of these reports (and of the presidency) ultimately affected management across the entire executive branch – cabinet secretaries and agency heads increasingly focused on these abstract goals. Departments created policy and planning units, and expanded their budgeting and personnel departments. The government became increasingly top-heavy and less focused on implementation.

But POSDCORB’s victory was not preordained. It won out against a competing theory of management, which was invented in World War II in response to the exigencies of total war.

Work Simplification and TWI

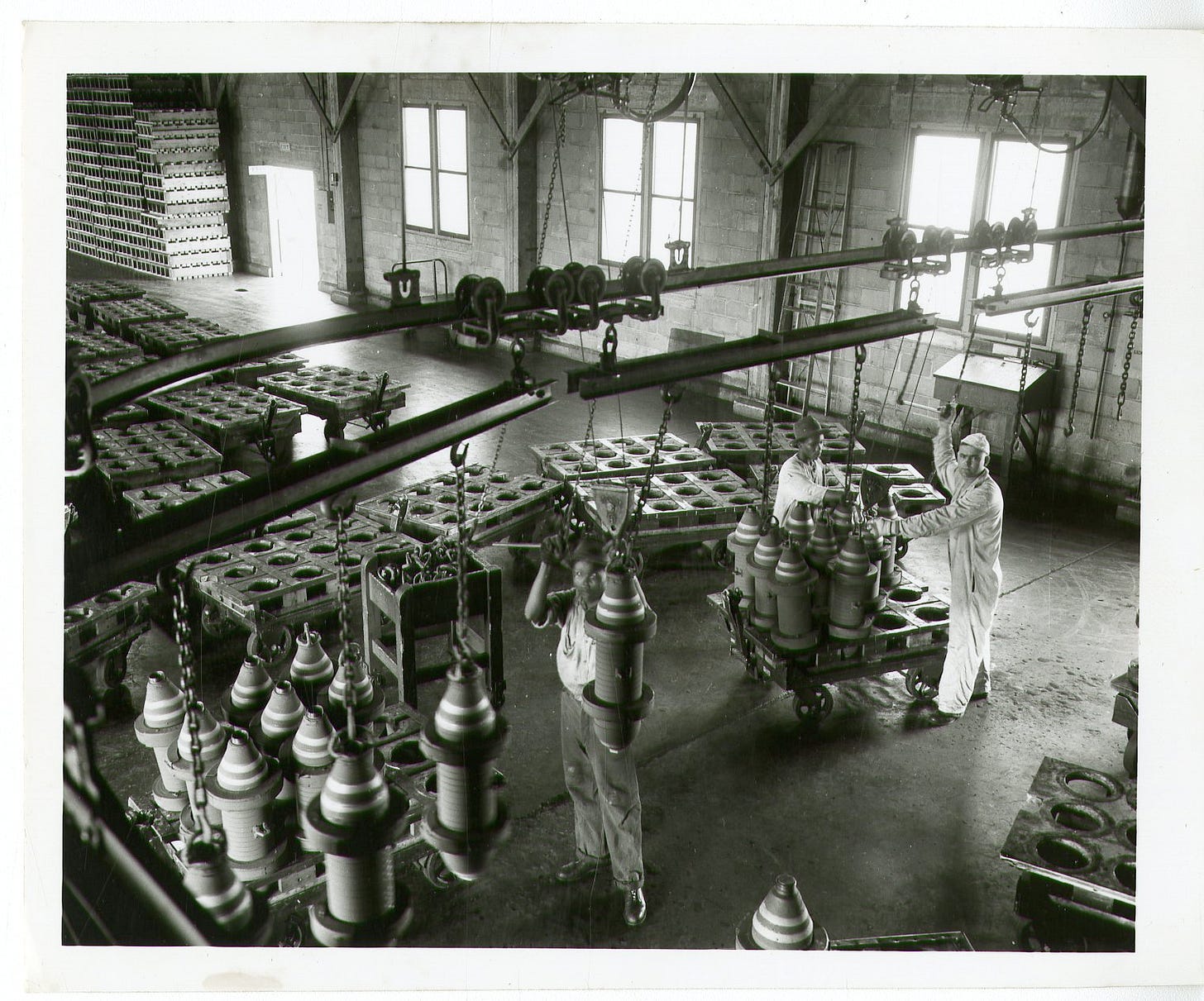

During WWII, the new war production plants needed to rapidly train line workers and managers. To assist with this problem, the federal government’s War Manpower Commission helped develop a standardized technique for industrial training, which they called Training Within Industry (TWI).

TWI covered many types of training, including managerial training. The TWI manuals focused on the lowest level managers – the supervisors – saying, “The supervisors are the key persons in the war production, home-front job.”3 The training then states that there are five main requirements for managers:

Knowledge of His Work.

Knowledge of Responsibilities.

Skill in Instructing.

Skill in Improving Methods.

Skill in Working with People.

This, too, could be used as a general theory of management. In fact, the federal government did use it as a general theory of management: Work Simplification was Training Within Industry as adapted for government managers.

There is once again no need to discuss the five requirements in detail, except that they focused on operations and implementation. Once again, this was a general theory of management – although the guides discussed the lowest level supervisors, it was a framework for managers at any level.

Of course, the top managers had to focus on other issues, too: executives undoubtably did budget, and plan, and organize, and all the rest. But the main focus of this approach was operational, with these other functions playing a supporting role.

Conversely, workers and low level managers were tasked with contributing to overall strategy by improving the organization’s processes. There was no theoretical line dividing policy from operations; everyone did a bit of both, although the top executives and the line workers were certainly at opposite extremes.

The TWI approach could even be adopted by chief executives of organizations, and in fact it was. Treasury Secretary Snyder used Work Simplification to achieve his policy goal of IRS reform: he whipped up enthusiasm by trusting line workers, worked with them to craft a minimal viable reform, and iterated until he had reorganized and modernized the agency. Empowering the lowest-level employees ultimately empowered the secretary.

For whatever reason, Training Within Industry was abandoned fairly rapidly after WWII. It lasted longer in the federal government, but was abandoned by the mid 1960s.

But it did find a receptive audience elsewhere. Training Within Industry proved popular in Japan; it was adopted by Toyota and rebranded as lean production.

So, a summary: the federal practices of the 1940s and 1950s were based on the immediate forerunner of lean production, a proverbially modern approach to management. This was replaced by a top-heavy approach focused on policy planning; few successful organizations use this approach today.

When reformers suggest abandoning failed reforms, the common response is that we cannot return to the past. The TWI history suggests a response: The past approach is sometimes the more modern and proven approach.

Gulick, Luther, and Lyndall Urwick, Papers on the Science of Administration (Routledge, 2004), 13.

POSDCORB somewhat fails at the basic purpose of an acronym, which is to be memorable.

The proposal led to the creation of the Executive Office of the Presidency (EOP) in 1939. Per POSDCORB, the budgeting agency was placed inside of it. The Bureau of the Budget (now OMB) was created in 1921, but it had been located inside the Treasury Department until its relocation to EOP.

Gulick’s proposals were more broadly successful than one might suppose: in 1939, the EOP had agencies not just for budgeting, but for planning, staffing, and reporting, too. All of these other agencies were abolished at various points before the end of the Truman administration.

War Manpower Commission: Bureau of Training, Management and Skilled Supervision: The Training Within Industry Program (June 1944), 1.